Drugscope provide a daily round up of news, research & opinion related to drugs to your email inbox. This is a useful way of keeping up to date, subscribe via this link.

My Crew is an organisation funded by the Scottish government which aims to provide impartial advice about drugs, This includes a risk checker where a young person can enter the name of a drug or up to three drugs at once and read information about the risks of using.

Volteface provide a useful summary of drug education programmes

Introduction

British Medical Journal, 2017. Novel psychoactive substances; types, mechanisms of action, and effects

Daly, M. 2017. This is why gen Z isn’t into drink or drugs

Degenhardt, L., Stockings, E., Patton, G., Hall, W.D. and Lynskey, M., 2016. The increasing global health priority of substance use in young people. The Lancet Psychiatry, 3(3), pp.251-264.

Donovan, J.E., 2004. Adolescent alcohol initiation: A review of psychosocial risk factors. Journal of adolescent health, 35(6), pp.529-e7.

Fergusson, D.M., Boden, J.M. and Horwood, L.J., 2008. The developmental antecedents of illicit drug use: evidence from a 25-year longitudinal study. Drug and alcohol dependence, 96(1-2), pp.165-177.

Hall, W.D., Patton, G., Stockings, E., Weier, M., Lynskey, M., Morley, K.I. and Degenhardt, L., 2016. Why young people’s substance use matters for global health. The Lancet Psychiatry, 3(3), pp.265-279.

Hamilton, I. 2017. Healthcare professionals need more guidance to reduce the risk of cannabis related health problems. British Medical Journal

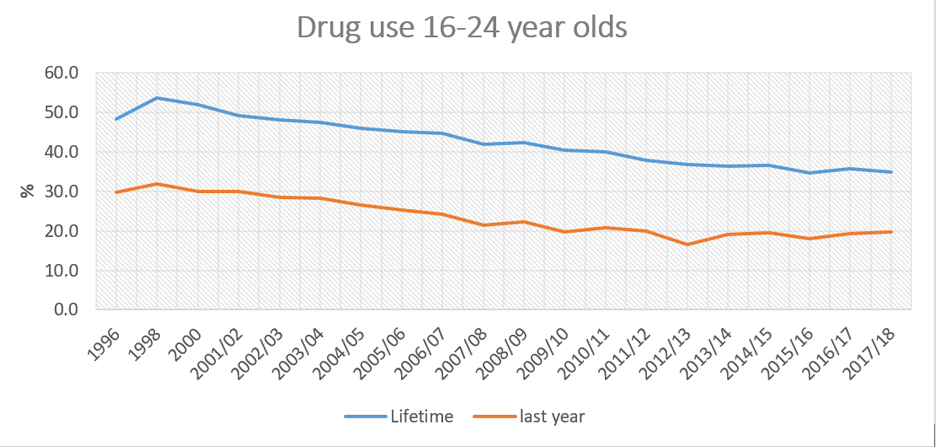

Home Office 2018 Drug misuse: findings from the 2017 to 2018 CSEW

LaScala, E., Freisthler, B. and Gruenewald, P.J., 2005. 2.5 Population Ecologies of Drug Use, Drinking and Related Problems. Preventing harmful substance use: The evidence base for policy and practice, p.67.

Mentor-ADEPIS

Nicholls, J., 2012. Everyday, everywhere: alcohol marketing and social media—current trends. Alcohol and alcoholism, 47(4), pp.486-493.

NHS Digital, 2017. Smoking, drinking and drug use among young people in England – 2016

Pennay, A., Livingston, M. and MacLean, S., 2015. Young people are drinking less: It is time to find out why. Drug and alcohol review, 34(2), pp.115-118.

Public Health England, 2017. What we know about young people in alcohol and drug treatment

Ramstedt M. Determinants of non-drinking among Euro-pean adolescents: a cross cultural comparison. Kettil BruunSociety Alcohol Epidemiology Symposium; Kampala, Uganda, 2013.

Stone, A.L., Becker, L.G., Huber, A.M. and Catalano, R.F., 2012. Review of risk and protective factors of substance use and problem use in emerging adulthood. Addictive behaviors, 37(7), pp.747-775.

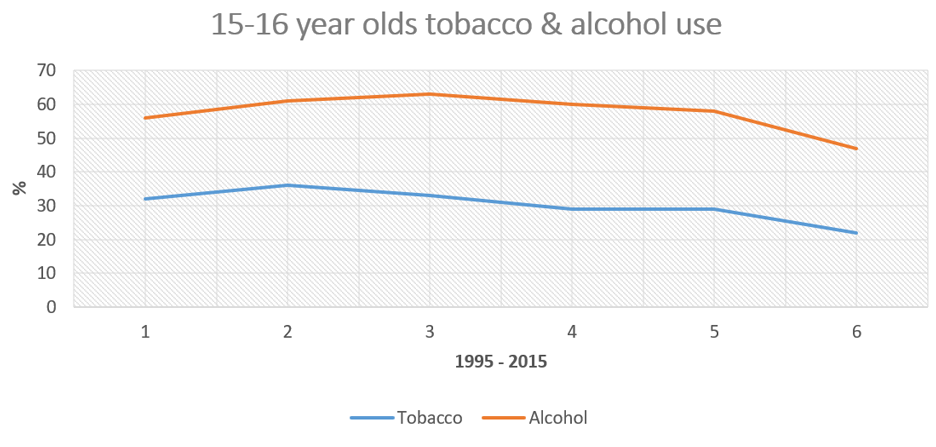

The European School Survey Project on alcohol and other drugs, 2016. Results from the European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs

van Laar, M., Frijns, T., Trautmann, F. and Lombi, L., 2013. Cannabis market: User types, availability and consumption estimates.

Winstock, A., Lynskey, M., Borschmann, R. and Waldron, J., 2015. Risk of emergency medical treatment following consumption of cannabis or synthetic cannabinoids in a large global sample. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 29(6), pp.698-703.

What we know already

Campbell, R., Starkey, F., Holliday, J., Audrey, S., Bloor, M., Parry-Langdon, N., Hughes, R. and Moore, L., 2008. An informal school-based peer-led intervention for smoking prevention in adolescence (ASSIST): a cluster randomised trial. The Lancet, 371(9624), pp.1595-1602.

College Centre for Quality Improvement, 2012. Practice standards for young people with substance misuse problems

Fletcher, A., Bonell, C. and Sorhaindo, A., 2010. “We don’t have no drugs education”: The myth of universal drugs education in English secondary schools? International journal of drug policy, 21(6), pp.452-458.

Hamilton, I., 2014. The 10 most important debates surrounding dual diagnosis. Advances in Dual Diagnosis, 7(3), pp.118-128.

Moustafa, A.A., Parkes, D., Fitzgerald, L., Underhill, D., Garami, J., Levy-Gigi, E., Stramecki, F., Valikhani, A., Frydecka, D. and Misiak, B., 2018. The relationship between childhood trauma, early-life stress, and alcohol and drug use, abuse, and addiction: An integrative review. Current Psychology, pp.1-6.

White, J. 2019. Frank friends

Areas of uncertainty

Miller, W.R. and Moyers, T.B., 2015. The forest and the trees: relational and specific factors in addiction treatment. Addiction, 110(3), pp.401-413.

Stockings, E., Hall, W.D., Lynskey, M., Morley, K.I., Reavley, N., Strang, J., Patton, G. and Degenhardt, L., 2016. Prevention, early intervention, harm reduction, and treatment of substance use in young people. The Lancet Psychiatry, 3(3), pp.280-296.

What’s in the pipeline

Hides, L., Quinn, C., Cockshaw, W., Stoyanov, S., Zelenko, O., Johnson, D., Tjondronegoro, D., Quek, L.H. and Kavanagh, D.J., 2018. Efficacy and outcomes of a mobile app targeting alcohol use in young people. Addictive behaviors, 77, pp.89-95.

Measham, F.C., 2018. Drug safety testing, disposals and dealing in an English field: Exploring the operational and behavioural outcomes of the UK’s first onsite ‘drug checking’ service. International Journal of Drug Policy.

Ward, J., Davies, G., Dugdale, S., Elison, S. and Bijral, P., 2017. Achieving digital health sustainability: Breaking free and CGL. International Journal of Health Governance, 22(2), pp.72-82.

Young Minds / Addaction 2017. Childhood adversity, substance misuse and young people’s mental health