In this Papers Podcast, Dr. Karen Mansfield discusses her JCPP Advances Editorial Perspective ‘Missing the context: The challenge of social inequalities to school‐based mental health interventions’ (https://doi.org/10.1002/jcv2.12165).

Karen’s work aims to apply solid research to understand, promote, and protect the health and wellbeing of children and adolescents, with a particular interest in the promotion of equity, inclusion, engagement, and agency.

Discussion points include:

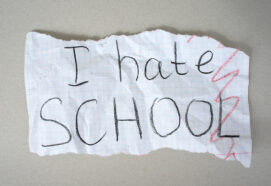

- The link between social economic adversity and children’s mental health.

- Scepticism around the impact and effectiveness of school-based intervention programmes.

- Potential issues of a ‘one size fits all’ approach and a ‘selective approach’.

- What to consider when designing interventions that both improve wellbeing and reduce inequalities.

- The challenges around measuring effectiveness.

- Potential policy shifts to consider and practical ways to improve children’s wellbeing in schools.

In this series, we speak to authors of papers published in one of ACAMH’s three journals. These are The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry (JCPP); The Child and Adolescent Mental Health (CAMH) journal; and JCPP Advances.

Subscribe to ACAMH mental health podcasts on your preferred streaming platform. Just search for ACAMH on; SoundCloud, Spotify, CastBox, Deezer, Google Podcasts, Podcastaddict, JioSaavn, Listen notes, Radio Public, and Radio.com (not available in the EU). Plus we are on Apple Podcasts visit the link or click on the icon, or scan the QR code.

Karen’s aim is to develop solid research to protect the health and wellbeing of children and adolescents, in collaboration with researchers from multiple disciplines, young people, policy makers, and all key stakeholders. Karen is particularly interested in the promotion of equity, inclusion, engagement and agency. Her research uses surveys, longitudinal data and co-production to investigate determinants of and factors associated with adolescent mental health, wellbeing, executive function, motivation and learning. Karen’s main affiliation is now at the Oxford Internet Institute, where she is working on a project with Andy Przybylski on Adolescent Well-being in the Digital Age.

From 2018-2022, Karen was a research scientist with the Oxford Health Biomedical Research Centre, carrying out translational research. Working closely with Mina Fazel, she led on development of the protocol, analysis plans, and dissemination of findings to stakeholders for the OxWell Student Survey, in collaboration with local authority and NHS partners. For the EMOTIVE project, Karen led on development of the protocol and experimental task for the collection and analysis of high-dimensional digital data to measure mood and emotions in patients and healthy volunteers (digital phenotyping). From May 2022 Karen worked on analyses of cohort data from the MYRIAD project with Willem Kuyken, including using measures that were co-designed with young participants from the trial. (Bio from Department of Psychiatry, University of Oxford)

Transcript

[00:00:01.329] Mark Tebbs: Hello, welcome to the Papers Podcast series for the Association for Child and Adolescent Mental Health, or ACAMH for short. I’m Mark Tebbs, I’m a Freelance Consultant. Today, I’m really pleased to be interviewing Karen Mansfield who is a Senior Postdoctoral Researcher at the University of Oxford in the UK. Karen aims to apply solid research to understand and promote and protect health and wellbeing of children and adolescents, with a particular interest in the promotion of equity, inclusion, engagement and agency.

Today, we’re going to be talking about an editorial piece at JCPP Advances, entitled “Missing the Context: The Challenge of Social Inequalities to School‐Based Mental Health Interventions.” The paper was a collaboration with Obioha Ukoumunne, Sarah-Jayne Blakemore, Jesus Montero-Marin, Sarah Byford, Tamsin Ford, and Willem Kuyken. Welcome, Karen, lovely to be speaking to you today.

[00:01:02.719] Dr. Karen Mansfield: Thank you so much for inviting me to talk about the editorial perspective.

[00:01:05.760] Mark Tebbs: Great stuff. So, could we just start with an introduction? Just tell us a little bit about your career to date, some of your work interests. It would be really interesting to understand what got you interested in children’s wellbeing, and that particular lens around social inequalities.

[00:01:22.020] Dr. Karen Mansfield: So, my background’s in experimental psychology, both research and some tutoring, as well, and my research areas have included cognitive, developmental, adaptive learning, and also, individual differences. And then I moved to adolescent mental health about five years ago, I’ve got three children, and the eldest was 12, so I’m very interested in the bidirectional relationships between cognitive and emotional health, and especially the impact that this has on learning, mental health, and longer-term outcomes. So, I think the role of social inequalities on both wellbeing and learning are far too often underestimated, and I think protecting young people’s health and wellbeing can prevent many mental health problems, and also, improve many other outcomes.

[00:02:00.020] Mark Tebbs: Thank you. Let’s turn to the editorial. Could you just give us a little bit of an overview?

[00:02:05.159] Dr. Karen Mansfield: Yeah, so the first half presents the challenges to effective school-based interventions, and so, these include poor health and wellbeing, and – which is, you know, reducing accessibility for many students. Also, persistent absence, and that’s often due to unsupported needs, and then lack of meaningful engagement in school or in interventions. And then the second half of the editorial sets out what our team agreed were the key priorities to address these challenges in future school-based mental health interventions.

[00:02:32.410] Mark Tebbs: Excellent, thank you. So, the paper describes that link between social economic adversity and children’s mental health. I suppose I’m just thinking about the context that we’re living in, so that post-COVID period of austerity. So, could you describe some of the recent research about that link between social economic adversity and children’s mental health?

[00:02:55.190] Dr. Karen Mansfield: So, there’s actually a team at UCL, led by Sir Michael Marmot, who’ve done a lot on this. So they’ve had some great papers, which looked at how health, so, basically, life expectancy, for example, has changed over the last years, and how other measures of children’s health have changed over the last years, with the priority being austerity. And then, with the pandemic, as well, then a lot of things have got a lot worse, with many parents, of course, becoming unemployed during that period, and then even more children suffering from poverty.

And then now, with the more recent economic crisis, then there’s been a lot of publications, not just by that team. There have been publications, for example, by ONS, and also, by organisations such as the Sutton Trust, who’ve been looking at the number of children who’ve been turning up at school hungry, for example, those who are eligible for free school meals. And it’s also these children who are eligible for free school meals, for example, who are more likely to experience poor attendance, or persistent absence, and so, there’s a huge link here.

[00:03:54.629] Mark Tebbs: Yeah, and obviously there’s a lot of work going on to try to address, kind of, children’s mental health, particularly the school-based programmes. The editorial mentions, like, that scepticism around some of the impact and effectiveness of those, could you tell us a little bit more about that?

[00:04:10.959] Dr. Karen Mansfield: Yeah, so there have been several school-based interventions that have been – well, quite a few actually, who’ve been unsuccessful or have had many small effects, but the scepticism really increased when the null results of the MYRIAD trial were published. And so, at the time I was working with the MYRIAD team, and there were several reasons for the failure of the MYRIAD intervention, and, in fact, the MYRIAD team are, kind of, looking into this from many, many different angles. Whereas, this editorial is more about the current challenges to school-based interventions, in general, so not specifically MYRIAD, but slightly broader than that.

[00:04:41.639] Mark Tebbs: So, there’s that sense that that one size fits all approach is unlikely to work as social disparities grow. Could you explain why you feel that the one size fits all approach might not be the best way to go?

[00:04:54.730] Dr. Karen Mansfield: Yeah, it’s not that – not necessarily that it isn’t possible to have a one size fits all, this is my opinion here, but that the way interventions are often designed, they are based on data which is collected often from not such diverse samples. And so those diverse samples that have been used to, kind of, understand the associations between mental health and learning and wellbeing and other factors, have not necessarily had a representative sample.

And so, this means that the way the intervention is designed might be effective for some group of people, the group of people who are most likely to take part in research, but not for the entire school population, or for the entire population of adolescents. And so, there’s such a broad range of needs, but research is not capturing all of that. And so, a lot of background research needs to be done to understand all of those needs, to understand how interventions can engage the kind of young people who don’t normally get engaged. And these are very often the young people who aren’t very much engaged in school, so those, for example, who are persistently absent, or just not engaging with school and lessons, in general, because those ones won’t be engaging with the interventions either.

[00:06:02.990] Mark Tebbs: Thank you. So, I guess what I really liked about the editorial was it also described the flipside of that, which is, there are also problems with a more selective approach. So, could you tell us a little bit about that too?

[00:06:15.910] Dr. Karen Mansfield: Yeah, so the selective approach, there’s quite a lot of reasons that I think are problematic. And so, one of them, first of all, is that it’s very difficult to identify a specific group of students who will benefit from an intervention. So, for example, do you give the entire population of school children a diagnostic scale to measure their mental health? You know, there are reasons why it might be good to do that, for screening, and so you can capture them, but, very often, you won’t capture all of them. So, some of them might not take part, some of them might not be totally honest, because they’re worried about privacy, for example, and saying that they have, for example, thoughts about death, and they don’t want this to come back to their Teachers or their friends or their families. And so, that makes it very, very tricky to identify exactly which groups of young people will most likely benefit from the intervention. So, then, you know, maybe we should take it broader, maybe we should offer it to everyone.

There’s also the thought of stigma, so, if you take one group of students out of a class, and you say, “Oh, you’re coming for our mental health intervention because we think you need it,” then this is going to make these children feel even worse about their own mental health. Everyone else is going to be looking at them, like, “Oh, they’ve got a mental health problem, they’re not normal,” and so there’s the stigma associated with that, as well. So, those are the key ones.

[00:07:31.650] Mark Tebbs: So, with those challenges in mind, what do we need to consider when we’re designing interventions that both improve wellbeing and reduce inequalities?

[00:07:40.270] Dr. Karen Mansfield: Yeah, so these are the priorities that we’ve set out in the editorial, which is about understanding what those unsupported needs are. So, which children are less likely to engage in the interventions? And these are probably the children who are less likely to engage in school, in general, so those, for example, who are persistently absent. You know, how do we understand what it is that’s making it difficult for these children to engage with school? How do we bring them back into school? How do we engage them? You know, that’s unlikely to be just forcing them back in, because it might get them in there physically, but it’s not necessarily going to engage them with the programme, or with any interventions going on in school.

And so, that might just be something simple, like ensuring that there are free school meals, especially in areas where you have a great deal of poverty. And offering that to everyone, because we don’t always capture – or, let’s say, those who are eligible to free school meals might not always be coming in and having those free school meals, so that’s a start. But, also, understanding what will engage those children more socially and emotionally, and they might feel very uncomfortable by something like mindfulness, but feel more comfortable with something like a sports intervention.

So, yeah, another way of getting at it, I suppose, which gets a little bit tricky when you come to measure it, is if you offer a choice of intervention. So, it might be that some children will benefit more from something which is a bit like mindfulness, while others might benefit from something which is art, sports, music, you know, there are all sorts of different things that can help children to engage socially and emotionally and improve their wellbeing, and, hopefully, protect them in the long-term.

So, I don’t know all of this research, this is what really needs to be done, so we need to investigate which children are not engaging, what might engage those children, what might benefit their mental health. As well as just the ones who would normally take part in, you know, in many, many research studies.

[00:09:27.149] Mark Tebbs: Yeah, you touched there on the measurement side, so what are some of the challenges around measuring effectiveness?

[00:09:32.940] Dr. Karen Mansfield: Some of the challenges with the effectiveness especially are if you are giving children a choice of intervention. So, then you get things like self-selection, and so it’s hard to know would this particular aspect of an intervention be beneficial to everyone? No, it probably wouldn’t. It would probably be beneficial to some and not to others.

But I feel like we’re at a stage now where there have been so many school-based interventions that have been tried, and if we use that data that’s already collected, so not just the MYRIAD data, but data from many, many interventions, to, kind of, understand which children have benefited from this, which children was this potentially harmful for? Then we might be able to use this to understand what range of interventions you can offer, and which kind of children might be more suited.

So, you can tailor it to schools, for example, you can know that in a school where there are a high degree of poverty and children might be coming into school hungry, you offer free school meals. In a school where, you know, you’re in a city, children might not be getting enough exercise, you might do something like that, so it’s about tailoring to schools, as well. But I was getting at how to measure it, and so, there are statistical methods for measuring this, where you take into account the extent to which each participant in an intervention fits into each aspect of it. It’s tricky. It’s very tricky.

I think it’s about – measure very well, I suppose, measure very well, all of the demographics of all of your participants. Understand also very well the extent to which they’ve engaged in each of those specific elements. It might be even that some days they’ve taken part in one aspect of the intervention, and other days, or months, or weeks, they’ve taken part in other aspects. So, yes, extremely complicated, and a challenge which, yeah, I can’t even get my head totally around it at the moment, so…

[00:11:19.899] Mark Tebbs: There’s such complexity there, and, clearly, sort of, more work that needs to happen, as well. So, I’m just wondering about, you know, policymakers, and how they, kind of, navigate this, whether there’s any policy shifts that the research suggests we should be moving towards?

[00:11:37.210] Dr. Karen Mansfield: So, I mean, there’s been some discussion around the extent to which free school meals for all is going to be beneficial. And I would say currently, “Yes,” because just offering it to those who appear to be eligible, then not everybody’s going to take it up, and so, it would be better to offer that more broadly.

I mean, the concern that you come into with this is that it’s all very, very costly, but that doesn’t necessarily mean – I think this is one discussion we had actually with the team, when we were writing the editorial perspective, just because something is costly, it doesn’t mean it’s not cost effective in the long run. By doing this when children are young and at school, if you can ensure that you are protecting their wellbeing and improving their health while they’re at school, and that might prevent all of those mental health problems, unemployment, so many outcomes, then it’s still going to be cost effective.

And so, I think in terms of policy, I think more focus on prevention and less focus on treatment when it happens, I think that’s – actually focusing on treatment is more expensive than doing the prevention in the long run.

[00:12:44.210] Mark Tebbs: And I’m just also thinking about that educational setting, does the research suggest practical ways of trying to improve children’s mental wellbeing in schools?

[00:12:54.690] Dr. Karen Mansfield: Well, there are some methods that are already proving to be successful sometimes, and that’s, for example, having somebody who’s a, like a trusted adult within schools. So, some of the research that I’m aware of that’s going on, that has proved to be beneficial. So, not necessarily saying, “Oh” – referring children to CAMHS, for example, but instead, just having someone that they can go and talk to. And that also emphasises agency, so children will be choosing, if there’s somebody there who they can talk to if they want to, they’ve decided themselves, and they’ve not been told in a way that might increase stigma from, “Oh, you know, you should go and see this person,” but they just have that option themselves, that’s one way of doing it.

But, I mean, also, more importantly, and I should have said this really on the policy question, not just on the schools question, but one of the solutions is about integrating. So, if there are different interventions going on, for example, in one school, or in one region, then that’s not going to be cost effective. But if you get all of those interventions together and you make it one large, complex, comprehensive intervention, then that, to me, makes sense.

Also, co-production, so many people seem to forget about this. If you talk to the people in the schools, so the Teachers, talk to the kids, talk to the parents, and make sure you get a real diverse, homogenous group involved in designing and choosing which interventions are going to take part in each schools, then you’re going to increase your chances of success. Especially if you want to reach those ones who don’t normally engage, because they’re often the ones who are more likely to benefit. So, yes, I guess it’s a – having a joined up approach, and not just somebody who’s the leader, who says, “Oh, we’re going to do this,” and makes the decision.

[00:14:36.250] Mark Tebbs: Brilliant, thank you. We’re coming to the end of the podcast, so I’m just wondering, do you have any follow-up research that you’re doing, anything you can share, work that’s coming up?

[00:14:46.861] Dr. Karen Mansfield: Not that I can share yet, but soon. So, there’s some – actually some exciting MYRIAD work, an exciting paper that’s reaping the benefits of some co-production work that was done by the MYRIAD team, and it’s absolutely fantastic. So, I can’t say too much about it at the moment, because we haven’t finished drafting it, haven’t got a final draft ready for submission, but soon, I will be able to.

So, young people have been involved very much in a lot of the work that happened during MYRIAD, and so, there were very many engagement activities, for example. And so, we’re looking at how – the extent to which those engagement activities benefited the young people and benefited the schools, and benefited the engagement with the research itself, as well. And some nice analyses of the data that we collected were co-produced by the young people, so that will be coming soon.

And, also, I – my research now, I’ve moved very slightly, so I’m now based at the Oxford Internet Institute. So I’m doing research which is more, I suppose, relevant to digital technology policies than it is to schools. But, later on, I’m hoping to integrate all of this work together, so I’m still very much interested in applying everything I’m learning in the school sphere.

[00:15:59.050] Mark Tebbs: Thank you. So, any final take home messages for our listeners?

[00:16:02.949] Dr. Karen Mansfield: That’s always a hard one.

[00:16:04.920] Mark Tebbs: Yeah.

[00:16:05.920] Dr. Karen Mansfield: Yeah, a take home message, I think we should be focusing on prevention, and rather than – well, I mean, there’s always – you always need treatment and it’s always going to be necessary, but let’s focus on prevention, and understanding that broad range of unsupported needs in young people. So, representative data and co-production.

[00:16:25.480] Mark Tebbs: Great stuff, thank you. Thank you so much, I’ve really enjoyed the podcast. For most details on Karen Mansfield, please visit the ACAMH website at www.acamh.org, and Twitter @ACAMH. ACAMH is spelt A-C-A-M-H, and don’t forget to follow us on your preferred streaming platform, let us know if you enjoy the podcast, with a rating or review, and do share with friends and colleagues.

Discussion

Thanks for the good work you are rendering globally

We are using this information for our intervations in Uganda.